Workers spend much of their time at work than in any other place. Like any other environment, the workplace is prone to health risks and hazards. Work-related injuries or diseases are obvious in any workplace. Globally, reports indicate that around 6,300 workers succumb to work-related injuries or diseases daily, [1] which is an average of 2.3 million fatalities annually. Fatal and non-fatal on-the-job accidents attributed to poor occupational safety and health practices were approximated at 337 million per year[2]. These accidents result to employee absenteeism from work for prolonged durations. Furthermore, there are over 160 million reported cases of occupational diseases, with a third of these cases resulting to at least four days absence from work annually. This leads to decreased productivity and performance, reduced revenue, and additional costs for compensating workers by firms. Such economic losses can be avoided, prevented, and controlled with the right measures put in place at the workplace. On households, some of the effects include increased dependency on other household members in cases where individuals are incapacitated and increased financial burden in cases where compensation is not forthcoming and loss of income/jobs.

The Constitution of Kenya (2010) Bill of Rights provides that every citizen has right to fair labour practices, reasonable working conditions and clean and healthy environment. The history of Occupational Health and Safety (OSH) in Kenya dates back to the 1950s when the need to have a legal instrument to manage the safety, health and welfare of factory employees became indispensable. The then British government adopted the British Factories Act of 1937. The Act was later amended in 1990 to Factories and Other Places of Work Act to widen its scope of coverage to additional workplaces initially not included under the Factories Act of 1937. Kenya has ratified and adopted 49 ILO Conventions out of which ten are OSH-related. The country compiled its first national profile on OSH in 2004, while the most recent one was compiled in 2013 (ILO, 2013). The profile provides labour market insights necessary for creating a safe and healthy workplace ecosystem in the country.

In 2007, the Factories and Other Places of Work Act was repealed and replaced by the Occupational Safety and Health Act (2007), [3] commonly known as OSHA 2007. In the same year, the Work Injury Benefits Act (WIBA) [4] was enacted. The Occupational Safety and Health Act promotes safety at workplace, preventing work-related injuries and sickness, while protecting third party individuals from being predisposed to higher risk of injury and sickness associated with activities of people at places of work. The Work Injury Benefits Act was enacted to ensure that workers who sustain work-related injuries and contract diseases that are work-related get compensated. Inspection and enforcement systems exist with a bearing to occupational safety, health, and labour inspections. Inspections related to environment at work, such as safety of workplaces, general health and basic welfare of workers are executed by the Directorate of Occupational Health and Safety Services – DOSHS – to ensure compliance with OSHA (2007). Specifically, the core roles of DOSHS include: inspection of workplaces to foster

compliance with safety and health law; measurement of workplace pollutants for purposes of their control; investigation of occupational accidents and diseases and aiming to prevent recurrence; examination and testing of steam boilers, steam and air receivers, lifts, gas cylinders, cranes chains among other lifting equipment; training on OSH, first aid and fire safety; approving of architectural plans of buildings intended to serve as workplaces; medical examinations of workers; and dissemination of information on OSH to employers, workers, other key stakeholders and the general public.

Further, there are other laws and regulations touching on OSH and are issued and enforced by other ministries and state departments. Such laws and regulations include: the Mining Act, Cap. 306, No. 2, 2009; the Biosafety Act, the Food, Drugs and Chemical Substances Act, Cap. 254; the Environmental Management and Coordination Act, No. 8, 1999; the Public Health Act, Cap. 242; the Employment Act, No. 11, 2007; the Energy Act, No. 12, 2006; the Radiation and Protection Act, Cap. 243 and the Standards Act, Cap. 496; the Pest Control and Product Act, Cap. 346; the Petroleum (Exploration and Production) Act, Cap. 308. In addition, the National Occupation Safety and Health Policy (2012) established national occupation safety and health systems and programmes designed to improve workplace environment.

DOSHS outlines that occupational accidents should be reported by an employer to the Director of Occupational Health and Safety Services on a prescribed form within 7 days following receipt of accident notice or on learning that an employee has been injured at work. In case of fatal accidents, the accident should be reported within 24 hours by fastest means possible and thereafter in writing to DOSHS within seven days.

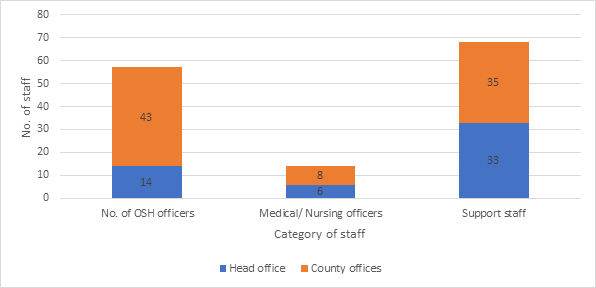

The total number of workplaces that are supposed to be inspected by the Directorate is estimated at 140,000, but only around 4,000 (2.9%) workplaces are inspected annually (ILO, 2013). Kenya has a population of 47.5 million people (KPHC, 2019), with a total working population of 18 million. About 3 million are employed in the formal sector and 15 million in the informal sector across the country (KNBS, 2020). DOSHS had 71 professional OSH officers (ILO, 2013). This is only 29 per cent technical capacity, and not sufficient to effectively inspect approximately 140,000 workplaces. This, therefore, leaves most workers exposed to OSH hazards. DOSHS has limited representation in the counties, with only 29 counties covered by the 43 technical staff members. The remaining 18 counties have no officers.

Figure 1: Distribution of DOSHS staff

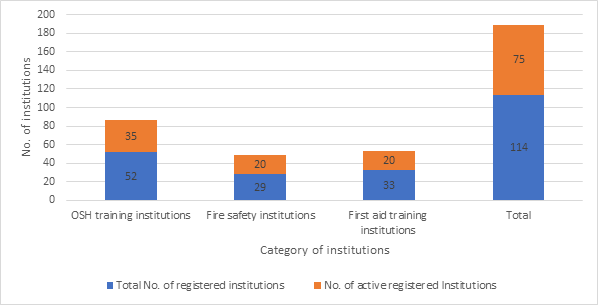

In Kenya, there are only 75 institutions that indulge in OSH training and awareness creation. This, in addition to master’s degree and postgraduate diploma courses offered by Jomo Kenyatta University of Science and Technology (JKUAT), is likely to increase the OSH awareness levels and uptake of OSH training at higher levels of learning, and thus impacting positively on the national OSH profile. The chattered OSH training and educational institutions are categorized into three: fire safety training institutions that provide basic fire safety training at workplaces, for instance fire marshals; OSH training institutions that train workplace OSH committees and increase OSH awareness; and first-aid training institutions that offer statutory basic first-aid course for workplace first-aiders. Figure 2 below shows the categories of OSH-approved training institutions.

Figure 2: OSH Approved training institutions

DOSHS also approves the skills and competency of technical persons involved in inspection of occupational safety and health at workplaces. Of the 329 registered and approved persons by 2012, only 60 per cent were active while the remaining 40 per cent were inactive for unknown reasons. This exacerbates the shortage of OSH human resources.

Table 1: Number of DOSHS approved technical persons under various categories